By Caitlin Coleman

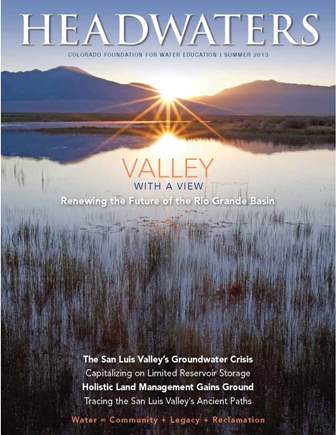

The Rio Grande flows 200 miles from southern Colorado’s high country before crossing into New Mexico, Texas, and Mexico—finally releasing into the Gulf of Mexico. Like all rivers that originate in-state, Colorado must share the Rio Grande’s waters with its downstream neighbors. In the San Luis Valley, the 75-year-old Rio Grande Compact governs all things water.

“The ultimate goal is to keep our depletion of the river the same as it was in the 1920s and 1930s,” says Craig Cotten, division engineer for Colorado’s Water Division 3, which administers water in the upper Rio Grande Basin.

Around the turn of the 20th century, irrigators in the San Luis Valley diverted much of the Rio Grande’s flow, worrying downstream states. From 1927 to 1936 engineers studied the river’s flows and uses; when it was signed in 1938, the compact adopted the results of those studies to fairly allocate the river between the three states.

With water storage becoming more critical than ever, Colorado's Rio Grande Basin moves to capitalize on existing reservoirs

By Caitlin Coleman

| For more on cooperative reservoir management at Terrace and at the Yampa Basin's Stagecoach Reservoir, listen to CFWE and Colorado Community Radio's Connecting the Drops audio coverage. |

Bruce Bagwell saunters into the Conejos Water Conservancy District office, housed in an old bank on Manassa’s Main Street. Bagwell casually nods hello to Nathan Coombs, who is busy at work, and pulls up a chair; he’s here to visit.

Bruce Bagwell saunters into the Conejos Water Conservancy District office, housed in an old bank on Manassa’s Main Street. Bagwell casually nods hello to Nathan Coombs, who is busy at work, and pulls up a chair; he’s here to visit.

“Right now, I’m working up the ambition to start a fire,” Bagwell says. It sounds like an expression, but isn’t. Bagwell is a ditch rider, hired by the Manassa Land and Irrigation

Company to maintain its irrigation channel and check on the headgates that allow water to flow, or not flow, off the ditch and onto private land. During irrigation season he drives up and down the Manassa system nearly all day long. In late March, Bagwell clears debris that filled the ditch over the winter, sometimes by burning it, to prepare for water to start flowing come April.

Coombs and Bagwell talk and laugh like old friends but both get more than good company from the visit—it’s about the water. The Conejos Water Conservancy District manages Platoro Reservoir, which can store nearly 60,000 acre feet of water to irrigate 100,000 acres of land. Much of the water that flows in the Manassa and other ditches along the Conejos, or beyond those ditches to reach the Rio Grande and flow out of state, is delivered from the reservoir.

The San Luis Valley's Race to Rebalance its Overdrawn Groundwater Supply

By Jerd Smith

| For more on the San Luis Valley's aquifers and to bring the story to life, listen to CFWE and Colorado Community Radio's Connecting the Drops audio coverage. |

Early on a March morning, high above the floor of the San Luis Valley, pale blue skies are just gaining light and the glamorous white peaks of the Sangre de Cristo and San Juan mountains form an elegant, fluted rim around the top of one of Colorado’s most productive farm regions.

Far below on the flats, it is a typical, early spring workday. Farm trucks roll up and down Highway 160 between Monte Vista and Alamosa, gas stations and seed stores open for business, and dozens of potato warehouse workers report for duty. This is big farm country, where the hard work of cultivating potatoes, barley, alfalfa, carrots and lettuce is done by people whose hands are rough and who wear uniforms of insulated coveralls and heavy work boots.

Rich in culture, this closely knit community of 50,000 people is locked in a fierce internal struggle over how to save itself from a historic water crisis. If left unresolved, the crisis could force state regulators to shut down hundreds of irrigation wells, crippling the valley’s robust farm economy.

At issue is an aquifer so stressed by overuse and chronic drought that it is in a virtual free fall. Since local water managers started monitoring in 1976, groundwater storage has dropped 1.2 million acre feet in the unconfined aquifer of the valley’s closed basin region. Some irrigation wells are so hampered by the aquifer’s decline that they can no longer pump, many surface water users with senior rights are being short-changed, and high commodity prices are making it difficult to convince people who still have adequate water to cut back their water use. “It really is a perfect storm,” says Steve Vandiver, general manager of the Rio Grande Water Conservation District, the local water agency that monitors groundwater levels and is now charged with raising them.

Holistic approaches to land management could sustain land, water and wildlife into the future

By Lauren Krizansky

Their methods are as diverse as the problems they are trying solve, yet the desired result is constant:keep the water flowing to keep life on the land. In the San Luis Valley, land managers face water shortages and environmental changes that could not only hinder the future of local agriculture, but also affect the quality and availability of wetlands and wildlife habitat.

Their methods are as diverse as the problems they are trying solve, yet the desired result is constant:keep the water flowing to keep life on the land. In the San Luis Valley, land managers face water shortages and environmental changes that could not only hinder the future of local agriculture, but also affect the quality and availability of wetlands and wildlife habitat.

In the foothills and mountainous regions to the east and west of the valley, decades of natural forest fire suppression have led to conditions now primed for massive, unpredictable burns. And along the southern reaches of the Rio Grande, unsupervised animal grazing is despoiling valuable riparian areas that serve as habitat for many species, including the endangered southwestern willow flycatcher.

These realities have some land managers turning to both historical and innovative practices that not only preserve what lives today, but also stabilize and enrich the many ecosystems— forest, farm and ranch—that make the San Luis Valley’s precious landscape productive and full of promise for coming generations.