|

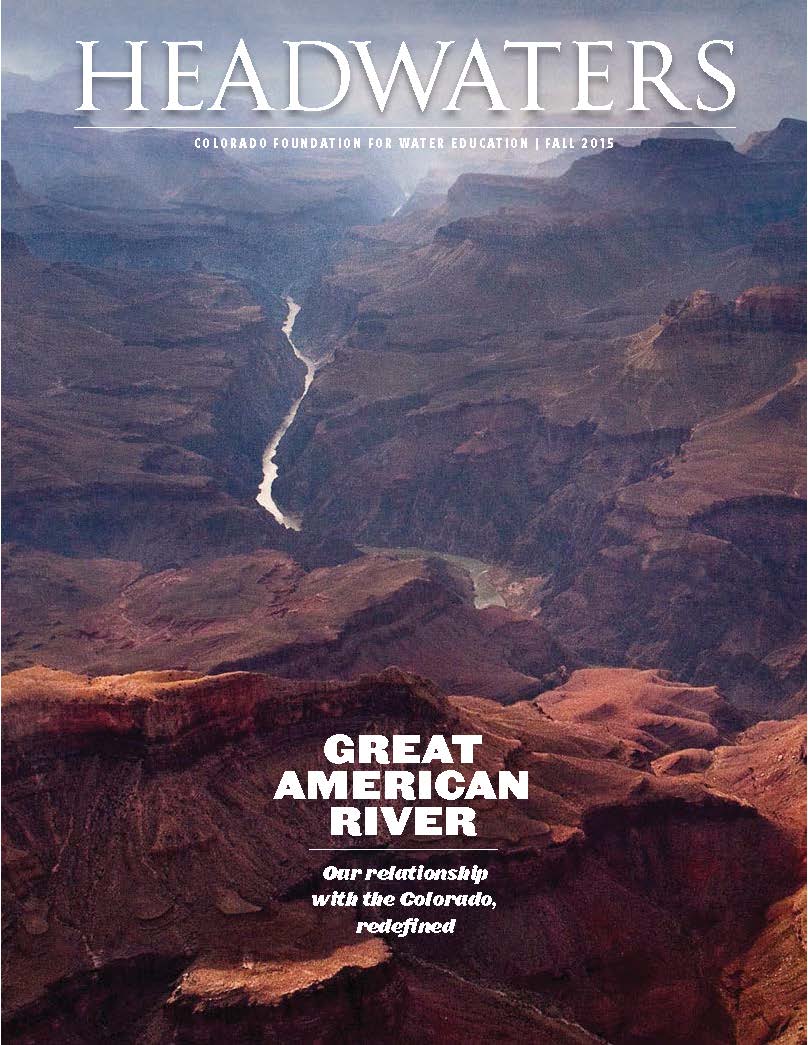

| Credit: Pete McBride |

Through administrative wrangling, risk assessment and contingency planning, Colorado is working to avoid the day—or brace for its arrival—when Colorado River water comes up short.

By Caitlin Coleman

Last winter, Colorado was in the news for uttering fighting words. Headlines like “Concerns over Colorado decision to keep all its river water” ran along the TV screen. At the time, an Associated Press story used a quote from Colorado Water Conservation Board director James Eklund making it sound like Colorado was flexing its muscle to prevent Colorado River water from flowing down to drought-stricken California. That aggressive, Colorado-centric stance was never Eklund’s intention.

The Southwest is tightly bound together by the vital blue cord of the Colorado River, which links the seven states and Mexico. “We’re joined at the hip,” Eklund says. In addition to his position with the Colorado Water Conservation Board, Eklund serves as Colorado’s commissioner on the Upper Colorado River Commission. The commission, created by the 1948 Upper Colorado River Compact, consists of five commissioners, one from each of the four Upper Colorado River Division states and one appointed by the federal government. It coordinates among the Upper Division states and works with the Lower Division on concerns that involve all river users, including ways to cope with drought and low reservoir levels in Lake Mead and Lake Powell. “This is kind of one of those ‘we all hang together or we all hang separately’ deals,” says Eklund.

For most states in the Colorado River Basin, the river is so essential that to “hang separately” is not an option. “If we’re not cooperating, the negative effects could just propagate like waves and we’d all be in a difficult position,” says Eric Millis, Utah’s Upper Colorado River commissioner and director of Utah’s Division of Water Resources.

It flows, but does it hold water?

By Nelson Harvey

To make conventional wisdom, take a grain of truth, lard it with a few misconceptions and throw in a preconceived notion or two. The result is the kind of simplistic belief that abounds in discussions of the Colorado River Basin, undergirding the idea that there is a silver-bullet solution for our water supply woes, that simply tearing up lawns, outlasting drought or building a pipeline will resolve our water problems. These notions, while easily bandied about at the dinner table, are hardly strong enough to inform a water policy, and close examination proves them false, or at least incomplete. With that in mind, we’ve set out to debunk six common myths about the Colorado River. Flowing through all of them is the most insidious myth of all: that the looming water shortages have any single cause, or any single solution.

Myth #1: We can shrug off the impacts to agriculture as municipalities work to acquire the water they need.

More than 70 percent: That’s how much of the Colorado River agriculture requires every year, making the sector an easy target for cities seeking to slake the thirst of growing populations. Yet if the “buy and dry” of agricultural land intensifies in the face of drought and growth, could it jeopardize food security?

According to a 2013 study by the Pacific Institute, a water policy nonprofit, about 15 percent of the nation’s food is grown with Colorado River water. Irrigated pasture, alfalfa and other feed for livestock occupy 60 percent of the basin’s agricultural acreage, while a smaller fraction—around 8 percent—is used to grow vegetables in places like California’s Imperial Valley and Coachella Valley and Yuma, Arizona. Those vegetables fill an important niche, accounting for up to two-thirds of the produce on grocery store shelves every winter, according to the Imperial County Farm Bureau.